More than a decade ago, Dr. Mojgan Rastegar gave the keynote address at an Ontario meeting focused on Rett syndrome, an incurable neurodevelopmental disorder.

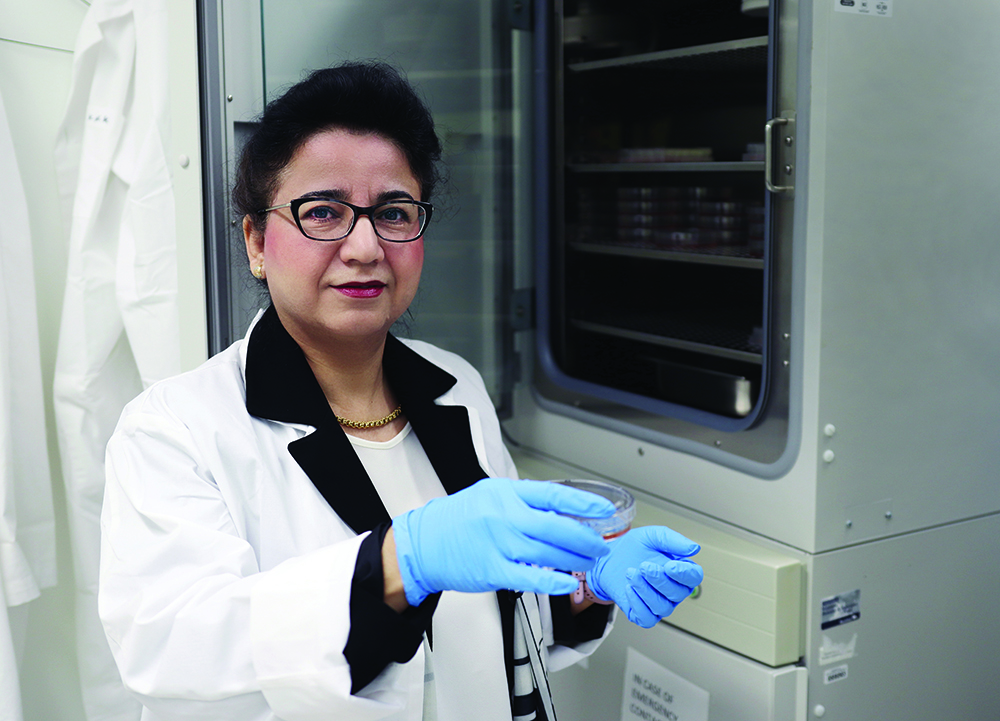

Rastegar, a UM professor of biochemistry and medical genetics, is an internationally recognized Rett syndrome researcher. At the time that she gave the address, her team had been studying the syndrome in transgenic mice for more than five years, trying to unravel its mysteries at the molecular and cellular levels.

The rare syndrome, caused by a random genetic mutation, occurs in one in 10,000 births, almost exclusively in girls.

A child who is affected generally seems like any other baby at first. But severe symptoms, including intellectual disability, loss of speech and seizures, start to appear at the age of six to 18 months. People with the syndrome, who need round-the-clock care, have varying lifespans.

Months after giving that talk in Ontario, Rastegar received an extraordinary phone call.

“It was a mother who had heard about me from the talk,” she remembers. “Her 12-year-old child with Rett syndrome was in the hospital. The child was expected to die within a few months. And this mother wanted to donate the child’s brain after death, so we could study it and learn from it.

“It was very surprising for me. To be honest, I was crying on the phone. She insisted that she wanted to entrust me with this donation.”

That remarkable gift started a long process that led to Rastegar founding the Human Rett Syndrome Brain Bio-Repository Laboratory at UM, which opened in 2019 and is unique in Canada.

With organizational support from the Ontario Rett Syndrome Association, Canadian families can now donate loved ones’ post-mortem brain tissues for study.

Rastegar is the principal investigator at the bio-repository, located at the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba, where she is also affiliated.

Asked about the rewards of her work, she says, “If I could help the Rett syndrome patients and their parents in any way, that would be my reward.”

Before joining UM in 2009, Rastegar earned her PhD in biomedical sciences in Belgium and did postdoctoral work at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, McGill University and Indiana University-Purdue University.

She has published 70 peer-reviewed articles in journals such as Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology, Molecular Autism and Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology.

Her lab continues to apply leading-edge techniques to investigating the molecular and cellular mechanisms that lead to compromised brain function in neurodevelopmental disorders.

We asked Rastegar three questions.

What attracted you to UM 16 years ago and led you to build your research program here?

I wanted to stay in Canada after my postdoc work, and I was very impressed with the infrastructure and capacity that UM had for the research program I wanted to establish. They were spearheading a regenerative medicine program, and I was very excited to work on stem cell biology.

I wanted to study the epigenetic control of stem cell differentiation in brain development. Epigenetics is what controls the switching on or switching off of genes inside cells.

When I started my lab here, I decided to combine my expertise in stem cell biology, epigenetics, brain development and neurodevelopmental disorders, and focus on diseases that affect children. Studying Rett syndrome brought all this together.

How would you explain your research in simple terms?

Rett syndrome is caused by a mutation of the MECP2 gene, the same gene that’s associated with other neurodevelopmental disorders – such as autism spectrum disorder and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder – that my lab has also studied.

Our team has made progress in understanding the role of a protein, MeCP2, made by this gene. Even though the protein was discovered more than 30 years ago, and science has known for more than 20 years that mutation of the gene causes Rett syndrome, we don’t know exactly what goes wrong in the brain.

Our lab is at the forefront internationally of studying post-mortem brain tissues from individuals who had Rett syndrome.

To complement the tissues we receive through donation, we have obtained additional Rett and non-Rett brain samples from the National Institutes of Health NeuroBioBank in the U.S. We are comparing Rett brains with non-Rett controls that are matched for age and sex.

We are now testing drugs in mice, targeting the molecules that are shared between mice and humans in terms of their abnormalities in Rett syndrome. We have some encouraging results that we will publish soon.

Because of your dedication to this research, have you gotten to know parents of children with Rett syndrome?

Yes, I have personal contacts with many parents. They reach out by phone and email. They share with me how their child is doing. I have a very open dialogue with them.

If they have medical questions, I refer them to doctors. But if they have scientific questions, I try to meet with them, either virtually or in person, and answer them. Even people from other countries have reached out with questions. Their questions and concerns contribute to shaping my research.

Parents who make the selfless decision to donate their child’s brain for our research say, “If not for my daughter, for the next generation of Rett syndrome patients, you may find some answers.”

BY ALISON MAYES