Dr. Jillian Horton was always a high achiever. Valedictorian of her medical class at McMaster University, she completed her residency in Toronto and became a successful physician in her home province of Manitoba.

But after more than 12 years in practice, the associate professor of internal medicine in the Max Rady College of Medicine had descended to a hard place.

The guilt and grief she carried, combined with the unrelenting pressure and exhaustion of medical training and practice, had left her numb. She wasn’t emotionally present for her husband and children, was losing compassion for her students, resented the medical system and felt she could never do enough for her patients.

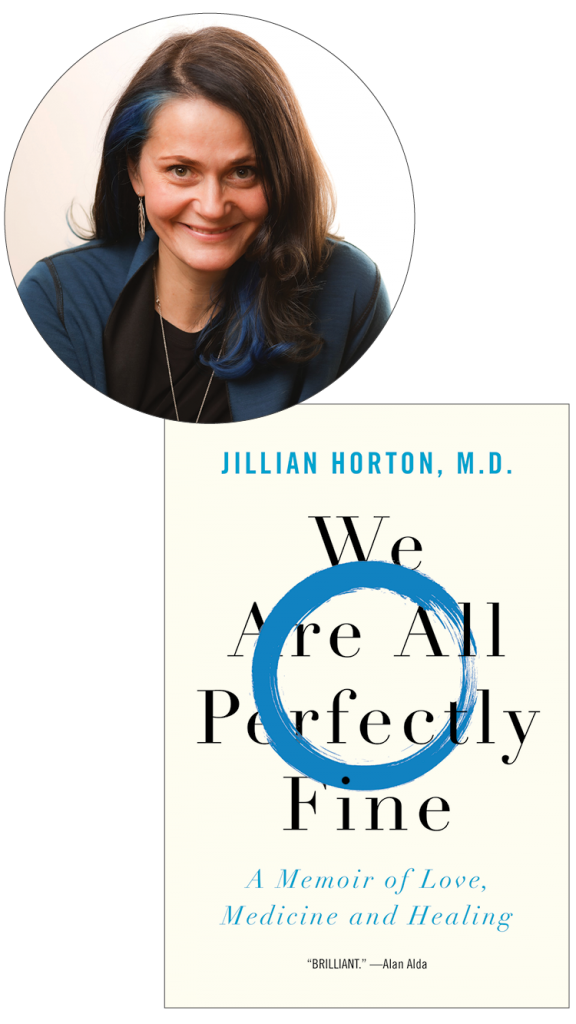

Reluctantly, Horton participated in a five-day meditation retreat for burned-out doctors. Her recently published book, the funny and wrenching We Are All Perfectly Fine: A Memoir of Love, Medicine and Healing, recounts how that experience opened the door to her recovery.

The memoir has been praised for its “deep reflections on the private suffering of the healing professions.” The following is an excerpt from the first chapter.

I’m a general internist, the kind of doctor who looks after people with medical problems that sound made up. Typhlitis. Neurocysticercosis. Ankylosing spondylitis. I also treat people with less exotic problems but lots of them at once. Heart failure and liver disease and sick kidneys. Stroke and pneumonia and severe mental illness. I work in an inner-city hospital, a rambling facility in need of a paint job, built on Treaty 1 land in a part of Canada that Truth and Reconciliation seems to have forgotten, a hundred miles from the town where I grew up. I look after people who are sick enough to be in the hospital. Some are dying. Many are homeless. Many are Indigenous and have been subjected to gross, almost unfathomable injustice, racial oppression and intergenerational trauma. They struggle to escape its legacy, which often comes in the form of drug and alcohol addiction.

I’m heading to a place in New York called Chapin Mill. Nobody’s sending me. I’m going of my own volition, unsure as to why, doubtful it will make any difference. In the only-in-my-mind major motion picture version of my life, either Hawkeye Pierce or the soulful doctor played by George Clooney on ER have staged an intervention, since it’s so painfully obvious to viewers that I’m floundering emotionally and need to go away somewhere for at least part of one season.

Interventions don’t happen in medicine, in my experience. When they do, they’re a late-stage measure, akin to chemotherapy for advanced-cancer patients who have no hope of cure. Most doctors look fine, perennially, until the day they don’t. That’s because doctors are excellent at compartmentalizing. We are also compliant and conscientious and rigidly perfectionistic, characteristics that put us at risk for choking to death on our own misery—or more specifically, overdosing on the perfect fatal combination of pills, throwing ourselves off just-tall-enough buildings, or slitting open the large arteries we studied so carefully when we were undergraduates, with the sleight of hand to bleed out quickly—if all goes well, in approximately five minutes.

I talk about death a lot; wouldn’t you? I’m surrounded it. I’ve signed more death certificates than cheques, and I pay for everything by cheque. Doctors have a delusional relationship with death. We trick ourselves into the professional assumption that death is reasonable. Not benevolent, but not unpredictable—nothing psycho about it. Birth on a good day is a Hitchcock film; death is often quiet, understated, like dealing with your accountant. So when it shows up on our doorstep, whether for us or one of our family members, suddenly this “reasonable” death that seemed so calm and inevitable when it was happening to other people turns out to be a real handful, and we’re often woefully unprepared to deal with it.

But we also talk and think so much about death because medicine is so f—ing hard.

Excerpt from “We Are All Perfectly Fine: A Memoir of Love, Medicine and Healing” by Jillian Horton ©2021.

Published by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.