The last time Manitoba’s First Nations communities saw widespread flu-like symptoms among their people, the outcome was grim. In 2009, the H1N1 influenza pandemic disproportionately affected Indigenous people, with higher rates of infection and over-representation among those needing hospitalization.

Generations of social, cultural and economic inequities have created obstacles to good health in these communities, from crowded housing to many people living with chronic health conditions and lacking access to consistent care. So when COVID-19 arrived in Canada, it was clear something different needed to be done to avoid another health crisis.

Rapid Response Teams is a concept designed and led by the Manitoba First Nations Pandemic Response Co-ordination Team (a partnership between the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakinak, First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba and Keewatinohk Inniniw Minoayawin). It is co-ordinated by the University of Manitoba’s Ongomiizwin – Health Services.

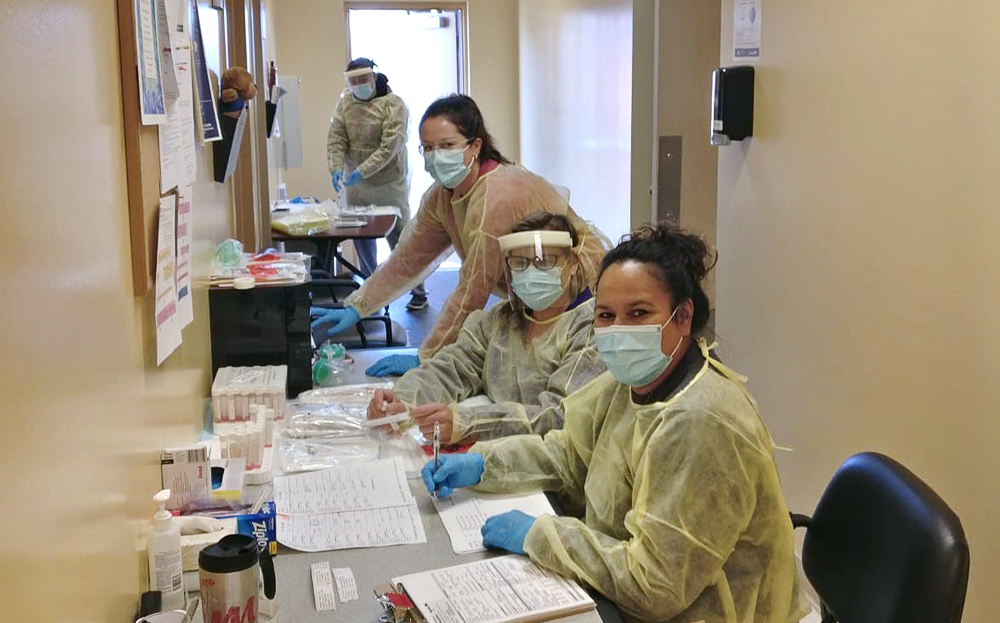

Interdisciplinary response teams of up to seven people are chosen from a network of health-care professionals – including doctors, nurses and rehabilitation specialists – that Ongomiizwin identified early on in the pandemic as being willing to respond to urgent needs in the community.

When the number of COVID-19 cases in a First Nations community exceeds, or is anticipated to exceed, what the local health workforce can manage, a rapid response team is quickly deployed – often within 48 hours.

“They [are deployed] knowing they are putting themselves into a riskier situation in service of our communities,” said Melanie MacKinnon [BN/96], executive director of Ongomiizwin, the Indigenous Institute of Health and Healing in the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences.

“They are the first people to really get a sense of how serious the situation is. Being on the ground, they have to identify and troubleshoot any challenges that are often not as apparent to those of us who support them from Winnipeg. This is a significant weight that they carry.”

Each team works in support of the local health workforce and with community leadership. In addition to supporting contact tracing, isolation planning and communications, the teams bring rapid point-of-care testing equipment, establish testing sites and schedule community members for testing, which has helped to contain clusters quickly.

Along with helping to deliver prompt, efficient care, the collaborative nature of the rapid response has also brought renewed confidence to First Nations communities.

“First Nations leadership for the rapid response teams is critical because it capitalizes on the health expertise, systems and community contextual knowledge, and relationships that First Nations leaders bring,” said Marcia Anderson [MD/02], executive director of Indigenous academic affairs for Ongomiizwin and vice-dean, Indigenous health of the Rady Faculty.

“It engenders a level of trust that results in teams being able to hit the ground running and deliver excellent, culturally safe care.”

Anderson added: “We have had really unprecedented collaborations in ensuring that we had this resource available to support communities. The National Microbiology Laboratory prioritized distribution of rapid point-of-care testing devices to remote First Nations communities, and the Public Health Agency of Canada has supplied field epidemiologists to assist us in assessing the larger outbreaks.

“We have had excellent support and collaboration with provincial medical officers of health, epidemiologists and regional health authorities. The way we’ve been able to leverage and access resources from others to support this First Nations-led response is a blueprint for all First Nations health service delivery in the future.”

As of the end of November, 12 rapid response teams had been deployed to communities as cases continued to rise. While First Nations people make up 10.5 per cent of Manitoba’s population, at that point they represented 19 per cent of active COVID-19 cases and 13 per cent of all deaths from the disease in the province.

BY HEATHER OLYNICK