In a landmark acknowledgment of the growing health-care autonomy of Indigenous Peoples, the federal government asked Ongomiizwin, the Indigenous Institute of Health and Healing in the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, to support timely access to vaccine by managing the COVID-19 vaccination project in all 63 Manitoba First Nations.

“We were asked to manage the vaccine rollout because of our strong collaborative relationships with First Nations and our expertise at delivering trusted, culturally safe care in our communities,” said Melanie MacKinnon [BN/96], a Cree nurse who leads Ongomiizwin and is executive director of its Health Services branch.

“Our goal is to get 100,000 first and second doses into 50,000 arms in 100 days,” MacKinnon said in March 2021. “I’m the co-lead of the operation with a senior federal government representative. So we’re not doing this instead of the federal government, we’re doing it with them.”

First Nations people on reserves were prioritized for vaccine access because of their high risk for severe illness and death if they were to contract COVID-19, and because social, cultural and economic inequities have created obstacles to good health in these communities. Elders in Manitoba had already been vaccinated before the project started.

The campaign was launched on March 20. By early June, at least 80,000 doses had been administered, MacKinnon said, and mass immunization clinics for adults were scheduled to be complete by mid-June. Clinics for 12-to-17-year-olds were underway.

“The University of Manitoba is the only university in Canada to be recognized as having the Indigenous-led clinical operations and public health expertise to direct a project on this scale,” said Brian Postl [MD/76], dean of the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences.

“This is a tribute to Ongomiizwin, which is at the forefront of building a new model that empowers Indigenous people to have greater authority over their own health care.”

Ongomiizwin – Health Services, formerly the J. A. Hildes Northern Medical Unit, has a 52-year track record of serving communities in northern Manitoba and Nunavut.

It has coordinated the Rapid Response health-care teams that have been deployed more than 120 times by the Manitoba First Nations Pandemic Response Coordination Team (MFNPRCT) to manage outbreaks of COVID-19.

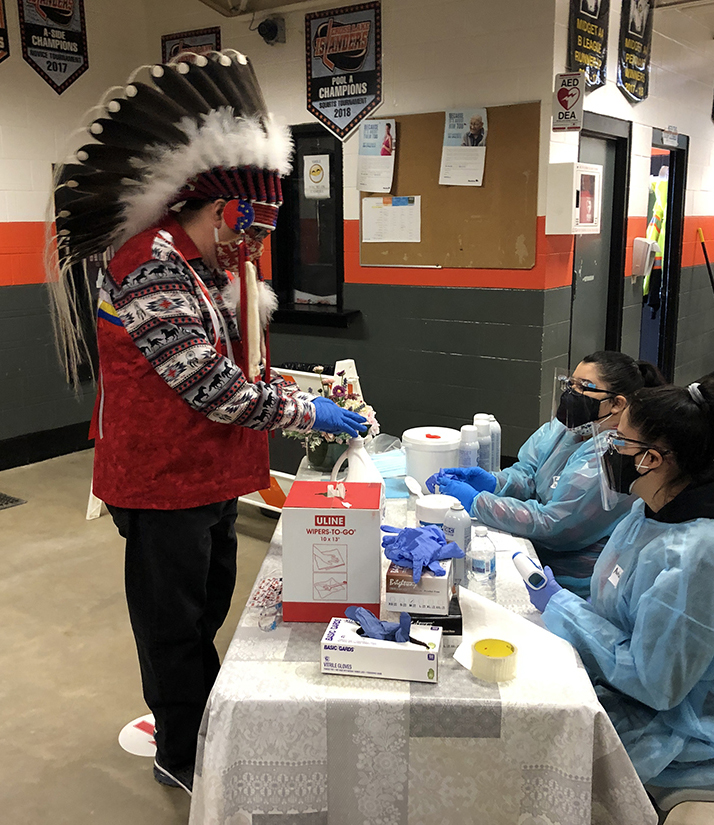

On-reserve vaccination clinics have been set up in facilities such as arenas and community halls, in collaboration with the local health workforce. At many clinics, MacKinnon said, each day has started with ceremonial smudging of the vaccine doses.

“They’re honouring the medicine as sacred – integrating physical and spiritual wellness,” she said.

Marcia Anderson [MD/02], a Cree-Anishinaabe physician, is vice-dean, Indigenous health of the Rady Faculty, executive director of Indigenous academic affairs for Ongomiizwin, and public health lead for MFNPRCT.

“Through collaboration between First Nations communities and organizations, the federal and provincial governments and the Rady Faculty, we have moved toward the collective vision of First Nations self-determination in health care,” she said.

Anderson has described the collaborative COVID-19 response as “a great example of what working in the spirit of reconciliation means.”

Ongomiizwin received a huge response to its call for health-care providers – including UM health sciences faculty – who were willing to drive or fly to First Nations for paid work as vaccinators.

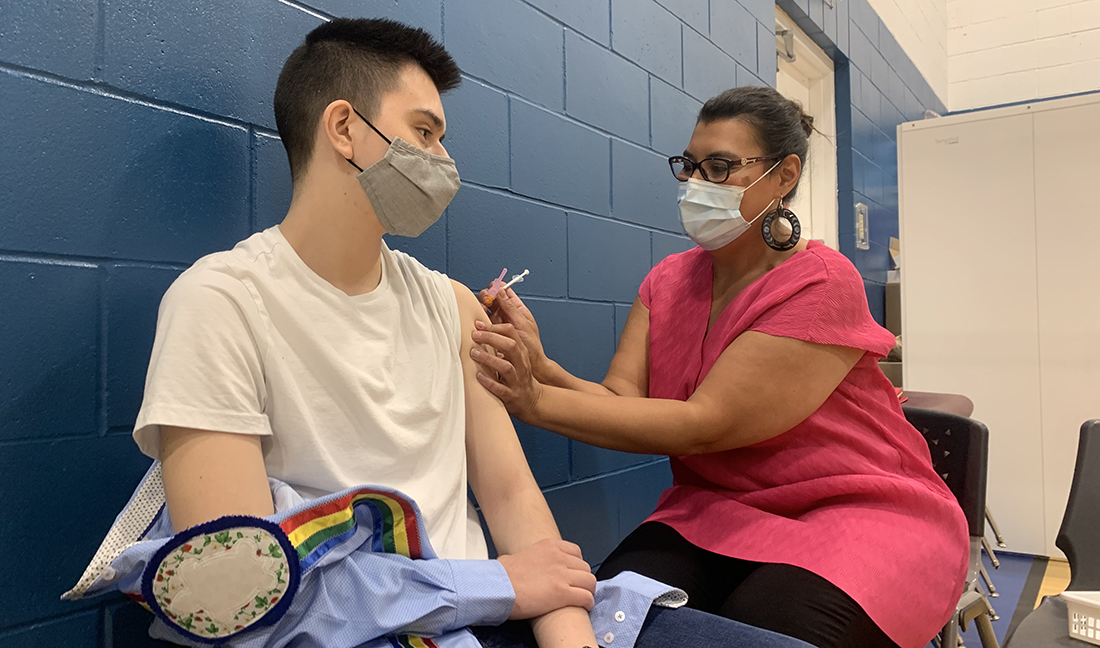

Kanisha Cruz-Kan [MD/19], a third-year UM resident in emergency medicine, was deployed in June to administer vaccines to youth in Long Plain First Nation.

“It was a great experience,” Cruz-Kan said. “The community health nurse and her team had made door-to-door visits prior to our arrival to inform the community about the availability of the vaccine and to answer any questions. I was glad to have participated.”

Describing the vaccination project as “momentous,” MacKinnon said, “I’m proud of communities’ own innovations and their efforts to vaccinate their community members. They all worked so hard.”

The rollout has been implemented in partnership with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC), Southern Chiefs Organization and Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak/Keewatinohk Inniniw Minoayawin.

“This is a testament to what can be achieved when all levels work together in unison for the good of all Manitobans,” said Grand Chief Arlen Dumas of the AMC.

Other organizations supporting the project include the federal government’s First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, Shared Health (Manitoba), the Canadian Armed Forces and the Canadian Red Cross.

Cultural connections increase off-reserve vax rate

The rollout of COVID-19 vaccines to First Nations is a success story that holds lessons for future health-care delivery to Indigenous populations, says Dr. Marcia Anderson, public health lead for the Manitoba First Nations Pandemic Response Coordination Team (MFNPRCT).

As of early June, the adult uptake rate for vaccination on Manitoba reserves was a strong 67 per cent. Anderson attributes some of the campaign’s success to ensuring that Elders, Knowledge Keepers and other leaders in the communities had the opportunity to be vaccinated early.

That way, they could inform and reassure others, helping to counteract the distrust that many First Nations people understandably feel toward government and the health-care system.

“We knew how important it was going to be to have valid and reliable information from trusted messengers,” Anderson told the Toronto Star.

First Nations people who live off reserve, however, have faced more barriers to accessing vaccines. Their adult uptake rate as of early June was 48 per cent.

Manitoba’s initial urban strategy was to rely on a few “supersites” with complicated advance booking systems, to which people were expected to travel. These mass clinics lack the cultural safety, level of trust, Indigenous staffing and ease of access that have made First Nations people comfortable on reserves, Anderson says.

In late May, data showed that the gap in COVID-19 infection rates between Black, Indigenous and other people of colour (BIPOC) and white Manitobans was widening as the white vaccination rate climbed.

On June 4, MFNPRCT announced that nearly 40 per cent of those who had died of COVID-19 in Manitoba in May were First Nations people.

Anderson says, however, that Urban Indigenous Vaccination Centres, now open in trusted cultural spaces in Winnipeg, Brandon, Portage la Prairie and Thompson, are making a difference.

The province should consider removing transportation barriers and offering more supports at these sites, such as medications for common side effects, food hampers and medicine bundles, the Cree-Anishinaabe physician told CBC.

Outreach efforts such as door-to-door campaigns would also help raise the rate, Anderson said in the Winnipeg Free Press. She called for “one-on-one conversations with people, answering any questions about the vaccine [and] ensuring people know where they can get the vaccine.”

RADYUM STAFF