Lisa Lix [M.Sc./91, PhD/95] took an unusual path to becoming an internationally recognized biostatistician.

Raised in Saskatchewan, she completed her first degree there in home economics, intending to pursue a career in clothing and textiles research.

Then, while earning her master’s in human ecology at UM, she was a teaching assistant for a statistics course taught by psychology professor Joanne Keselman [BA/73, MA/75, PhD/78]. Lix was hooked on statistics after working with Joanne, who then introduced her to her husband, psychology professor Dr. Harvey Keselman.

Harvey became Lix’s PhD supervisor. She credits him with her enthusiasm for research, attention to detail and work ethic.

“He pushed me to strive to be a top researcher,” she says.

Lix joined the UM faculty in 2001, left for the University of Saskatchewan in 2008, and was recruited back to UM in 2012.

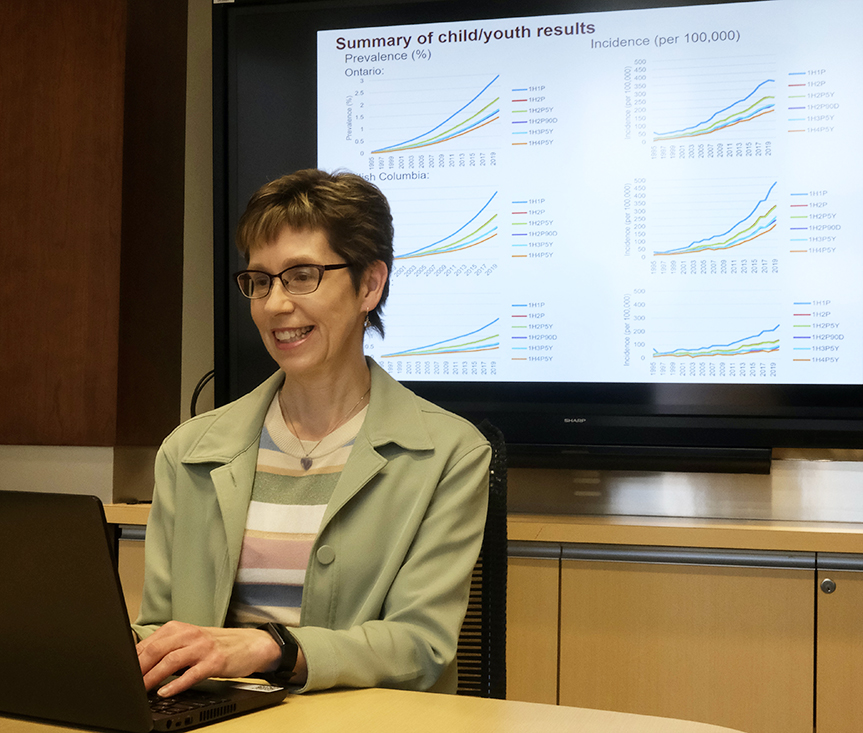

Today, she is a professor of community health sciences at the Max Rady College of Medicine. She holds a prestigious Canada Research Chair in methods for electronic health data quality, is a senior research scientist with the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and directs the Data Science Platform at the George and Fay Yee Centre for Healthcare Innovation.

Lix has led the way in research that examines the quality of large, anonymized health-care databases, which are increasingly used for studies of population health and health service use.

Many databases contain health-care records that were never intended to be used for research. Lix studies how accurate and complete datasets are, and whether they can be used for reliable and valid studies. She is a particular expert on statistical models to improve research about chronic conditions, such as osteoporosis.

While there are now other researchers probing the limitations of health data, when Lix started, this was an under-recognized area of study. People assumed that the size of databases outweighed any problems with their quality, she says.

“As my graduate students and I started to look at these databases, we found that no amount of data can outweigh poor-quality data. Just because you have a lot of data doesn’t mean that it’ll be helpful in answering your questions.”

One of the most important steps in any data collection or analysis project, Lix says, is to record the steps taken to collect and analyze the data. She encourages her students to write detailed analysis plans.

“These plans are living documents that are updated as decisions are made,” she says. “They are invaluable when it comes to writing a scientific paper or a report for government.”

It’s also vital, she says, to spend time getting to know the data before making decisions about analysis methods. “Real-world data may not conform to the assumptions that underlie conventional statistical models.”

Lix is now exploring artificial intelligence and machine learning to help extract information from health data. “That wasn’t even thought of five years ago,” she says.

Being an innovator in her field attracts graduate students, but she doesn’t take that for granted.

“The enthusiasm that comes from working with very bright, new-to-research students just thrills me,” she says.

BY MATTHEW KRUCHAK